Tarka and Bunting

I’m not sure why I’ve never read Tarka the Otter before now. One of my favourite books as a kid was The Little Grey Men by ‘BB’ (published fifteen years after Tarka, in 1942), which - I realise now - is pretty much a retelling of the same story in the same setting: a riverside world unimaginably rich with life, slowly succumbing to the pervasive influence of man, through which our heroes are hunted mercilessly. ‘BB’ replaces otters with gnomes, and dials down the bleakness - whilst also offering less of Williamson's poetic sublimity. Tarka has a stark, deep coldness, in which the (only slightly) anthropomorphic animals survive - or don’t - in the face of an uncaring and Godless universe. There's a powerful sense of time moving on two linked but distanced levels - the ancient, slow time of the stars, and the rapid movement through life and death marked out by the heartbeats of ephemeral life:-

By night the great stars flickered as with falcon wings, the watchful and glittering hosts of creation. The moon arose in its orbit, white and cold, awaiting through the ages the swoop of a new sun, the shock of starry talons to shatter the Icicle Spirit in a rain of fire. In the south strode Orion the Hunter, with Sirius the Dogstar baying green fire at his heels. At midnight Hunter and Hunted were rushing bright in a glacial wind, hunting the false star-dwarfs of burnt-out suns, who had turned back into Darkness again.

Beneath all this, the otters strive for survival in a winter of ravishing hardness, in which the old otter dog Marland Jimmy dies, frozen with his head half in and half out of the ice, and the survivors blister their tongues as they lick at snow and ice to quench their thirst.

Another reason why this passage stood out for me is its surprising similarity to some of the final part of Basil Bunting’s long autobiographical poem Briggflatts (1965), which, like the passage from Tarka, is located in a wintry, coastal landscape:

Orion strides over Farne.

Seals shuffle and bark,

Terns shift on their ledges,

Watching Capella steer for the zenith,

And Procyon starts his climb.

Williamson's Orion strides in the south, with Sirius "baying green fire at his heels", while Bunting's Orion strides over Farne, and his Sirius "glows in the wind... lures for spent fish". Bunting’s fifty years of separation from his childhood love is made timelessly inevitable by the same distanced connection between ephemeral life on earth and ancient starlight: “The star you steer by is gone... light from the zenith / spun when the slowworm lay in her lap / fifty years ago".

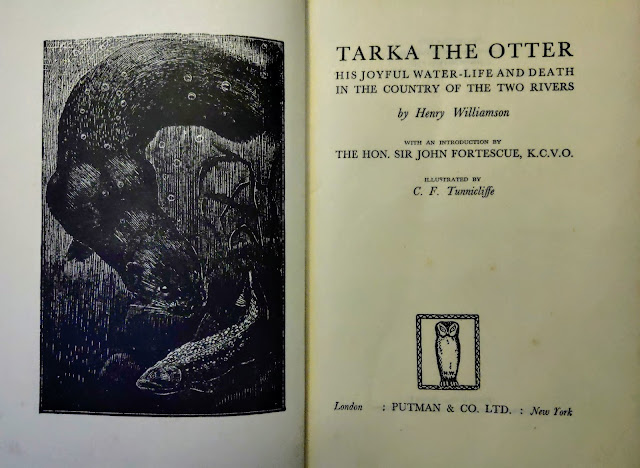

I’m glad I finished Tarka before I found out that Williamson was a follower of Oswald Moseley, and seems to have been unrepentant in his admiration for Nazi Germany even into the 1960s. It doesn’t diminish the power of the book, but that stark coldness gets a little sharper and a little darker. Are we to understand that it's only right - the natural order of things - that the otters should die at the hands of man, the strongest taking what is due to them? Note the sub-title in the title page above: his joyful water-life and death. The joy is not necessarily Tarka's, but a kind of abstract joy - the joy of universal life and death, in all its unsullied purity. But it's still a puzzle how something so alive with such rapt attention to the fullness of nature could have such black associations. I don’t know that it’s necessary to go further down this path: art can obviously stand apart from its creators. And Tarka’s extraordinarily empathetic portrayal of animal consciousness, and its depiction of humans harrying nature to its destruction, was an acknowledged influence on Rachel Carson, who in the 1960s wrote the devastating ecological warning Silent Spring – a text which grows in importance by the day.

Comments

Post a Comment